In Defense of the SAVE Act

Compared to what the people of Cambodia, Hong Kong, Thailand, and Myanmar have endured—what, exactly, are Americans being asked to sacrifice? A form. A certificate. A minor administrative update.

How much is liberal democracy worth?

That question is not rhetorical—not when, in many parts of the world, people have risked prison, torture, and death for the simple right to cast a vote in a free and fair election.

In Cambodia, democracy dangled like a cruel joke—always just out of reach—until it was torn away with brutal finality. After the 2013 national election, which the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) denounced as a sham, thousands of angry citizens, especially the youth, poured into the streets of Phnom Penh. They weren’t crusading for some bloody revolution. They were begging for something far more dangerous to a corrupt regime: truth. Transparency. The audacious idea that votes should actually matter. The government’s answer? Riot gear. Rubber bullets. Prison cells. Blood on the pavement. In 2017, under pressure from Prime Minister Hun Sen’s regime, the Supreme Court dissolved the CNRP entirely, snuffing out the last pretense of competitive democracy. What’s left today is a parody of an electoral process—a hollow performance staged by a dictatorship that no longer bothers to hide its contempt for democracy.

In Hong Kong, the 2019 pro-democracy protests began as opposition to an extradition bill but quickly grew into a movement about something deeper: the right to self-determination. Protesters clamored for democratic reforms, freedom of expression, and genuine suffrage. They were met with tear gas, batons, and sweeping arrests. Beijing’s imposition of the National Security Law in 2020 effectively criminalized dissent. Elected pro-democracy lawmakers were purged. Activists were jailed. Even organizing a candlelight vigil became a subversive act. For Hongkongers, the ballot was the battleground. And when that ground was lost, so was everything else.

In Thailand, waves of youth-led protests erupted in 2020, demanding constitutional reform, greater government accountability, and curbs on the monarchy’s unchecked power. Far from riots, these were orderly calls for democratic renewal, led by students, artists, and civil society groups. The government retaliated with arrests, censorship, and the use of the kingdom’s archaic lese-majesté laws to silence critics. Activists vanished. Others faced years behind bars. Their plea was modest: a democratic say, and a system that honored it.

Then there’s Myanmar, where in 2021, the military annulled a democratic election it didn’t like and launched a coup. The Tatmadaw arrested elected leaders, including Aung San Suu Kyi, and declared martial law. In the months that followed, unarmed civilians staged mass protests in what became known as the Spring Revolution—a national outcry against authoritarianism. The junta’s response was pure savagery: live rounds, mass killings, and detentions. By 2024, more than 4,000 people had been killed, and thousands more had disappeared or languished in prison. All because they believed their votes should mean something.

In each of these places, people weren’t agitating for utopia. They weren’t asking for luxury, prosperity, or perfection. They were asking for representation. For the right to choose their leaders without coercion, corruption, or fear.

Now contrast that with the United States—a nation where voting is a protected right, not a mortal gamble. And yet, we find ourselves in a bitter debate over the SAVE Act, a bill that would require Americans to present proof of citizenship to vote in federal elections. Critics call it voter suppression. They say it is burdensome. But compared to what the people of Cambodia, Hong Kong, Thailand, and Myanmar have endured—what, exactly, are Americans being asked to sacrifice?

A form. A certificate. A minor administrative update. If liberal democracy is worth dying for elsewhere, surely it's worth a little paperwork here.

That’s where the SAVE Act comes in.

Short for the Safeguard American Voter Eligibility Act, the SAVE Act was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives in early 2025. Its goal is to amend the National Voter Registration Act of 1993 by enforcing stricter requirements for registering to vote in federal elections. Having passed the House on April 10, 2025, the bill is now under consideration in the Senate.

At its core, the SAVE Act sets forth several key provisions. First, it stipulates that all applicants must provide documentary proof of citizenship (DPOC) when registering to vote. Acceptable documents include a REAL ID-compliant form of identification indicating U.S. citizenship, a valid U.S. passport, a U.S. military ID paired with a service record showing birth in the United States, or a government-issued photo ID stating a U.S. place of birth.

Other acceptable combinations include a photo ID with supplemental documents such as a certified birth certificate, hospital birth record, adoption decree, Consular Report of Birth Abroad, Naturalization Certificate, or an American Indian Card bearing a “KIC” classification.

Second, the bill prohibits states from accepting or processing voter registration applications for federal elections unless the applicant provides one of the approved DPOC documents. This stipulation applies to all forms of registration—by mail, online, or in person. For individuals who do not possess one of the specified documents, the bill mandates an alternative process: applicants must sign an attestation under penalty of perjury affirming U.S. citizenship and submit other evidence deemed acceptable by state officials. The Election Assistance Commission is tasked with issuing guidance on what qualifies as sufficient evidence.

Finally, the Act includes enforcement measures. Election officials who register individuals without the prescribed DPOC could face civil liability and criminal penalties, including fines and up to five years in prison.

For quite some time, a considerable segment of the political Left has treated voter ID laws like the coming of the apocalypse, reflexively opposing any initiative—be it for registration or in-person voting—that even hints at confirming someone’s identity. Their resistance isn’t subtle, either. Just four House Democrats voted in favor of the SAVE Act, a fact that speaks volumes. And the moment the bill cleared the House, progressive pundits and social media influencers scrambled to reframe it as the next battle in the culture war over gender politics. Legacy media, ever eager to amplify the frenzy, dutifully followed their lead—spiraling into a full-blown meltdown and plastering the airwaves with breathless, doom-laden headlines like: “House GOP Tramples on Women’s Rights with Passage of SAVE Act” and “Married Women Could Be Stopped from Voting Under SAVE Act.”

This hysteria rests on a wildly misleading premise: that because nearly 80% of women in opposite-sex marriages adopt their husband’s surname—resulting in inconsistencies between their birth certificates and current photo IDs—they’d be turned away en masse at the polls. Yes, millions of Americans change their names for marriage, divorce, or personal choice. That’s not news. But a discrepancy in documentation is not tantamount to voter suppression. It is bureaucracy—tedious, perhaps, but not tyrannical. To conflate administrative inconvenience with disenfranchisement is not just lazy thinking; it is a category error—one that cheapens the gravity of real voter suppression by stretching the term so thin it becomes meaningless, a hollow buzzword deployed more for political theater than genuine advocacy.

And much to the dismay of the outrage machine, a straightforward reading of the bill is enough to make their narrative crumble. There is a clear, plainly titled provision—“Process in case of certain discrepancies in documentation”—that spells out exactly how such issues should be handled:

Subject to any relevant guidance adopted by the Election Assistance Commission, each State shall establish a process under which an applicant can provide such additional documentation to the appropriate election official of the State as may be necessary to establish that the applicant is a citizen of the United States in the event of a discrepancy with respect to the applicant’s documentary proof of United States citizenship.

But of course, why let facts get in the way when there is a sensational moral panic to inflame?

To date, the Election Assistance Commission has not provided official guidance on what constitutes adequate documentation in cases of legal name changes—a silence that fans the flames of the Left’s electoral Armageddon maelstrom. However, this is not uncharted territory. In the United States, there is typically an official record documenting any legal name change: a marriage certificate—issued by the county clerk or relevant authority—serving as the formal link between a person’s former and new name; a court-issued name change order, often used for gender transitions or personal preference; or a divorce decree with a name restoration clause. It stands to reason that any of these documents should, by any rational standard, suffice as valid evidence of name linkage.

In fact, Arizona already executes a statute requiring proof of citizenship for participation in state and local elections. And despite warnings of chaos or widespread disenfranchisement, the process has proven to be workable. A voting applicant may satisfy the criterion by submitting “a legible photocopy of the applicant’s birth certificate that verifies citizenship to the satisfaction of the county recorder.” In cases where a name mismatch occurs—such as when a woman adopts her spouse’s last name after marriage—the applicant must provide supplementary documentation, like a marriage certificate, to resolve the discrepancy.

This is not a hypothetical burden; it is a policy framework already operative in one of the nation’s most demographically diverse and populous states. While it introduces minor logistical challenges during the voter registration process, such inconveniences must be weighed against the overarching imperative of preserving the sanctity of democratic elections. What Americans are being asked to give up is not liberty, privacy, or equality—it is, quite simply, a brief afternoon at the DMV. If even a modicum of obligation is deemed too high a price to pay for upholding the integrity of our liberal democracy, then perhaps the problem lies not with the policy itself, but with our collective sense of civic responsibility.

It is worth stepping back to examine the current state of voter registration and identification policies. Given the vitriolic opposition to the SAVE Act, one might assume that the existing system is already fortified with rigorous screening protocols. In reality, that is far from the case.

Under the National Voter Registration Act of 1993, individuals are not bound to submit documentary proof of citizenship or identity in order to register to vote. Instead, applicants just have to sign an attestation, under penalty of perjury, affirming that they are U.S. citizens. No identification is needed—no passport, no driver’s license, not even a library card. The system, in essence, operates on the honor principle, entrusting everyone to self-certify their citizenship without immediate confirmation.

Although states are responsible for administering elections and might impose additional regulations, those measures must remain consistent with federal law. That is why Arizona’s regulation concerning proof of citizenship applies only to state and local elections. In Arizona v. Inter Tribal Council of Arizona (2013), the Supreme Court held that states cannot mandate documentary proof of citizenship for voters using the federal registration form unless granted explicit approval by federal authorities.

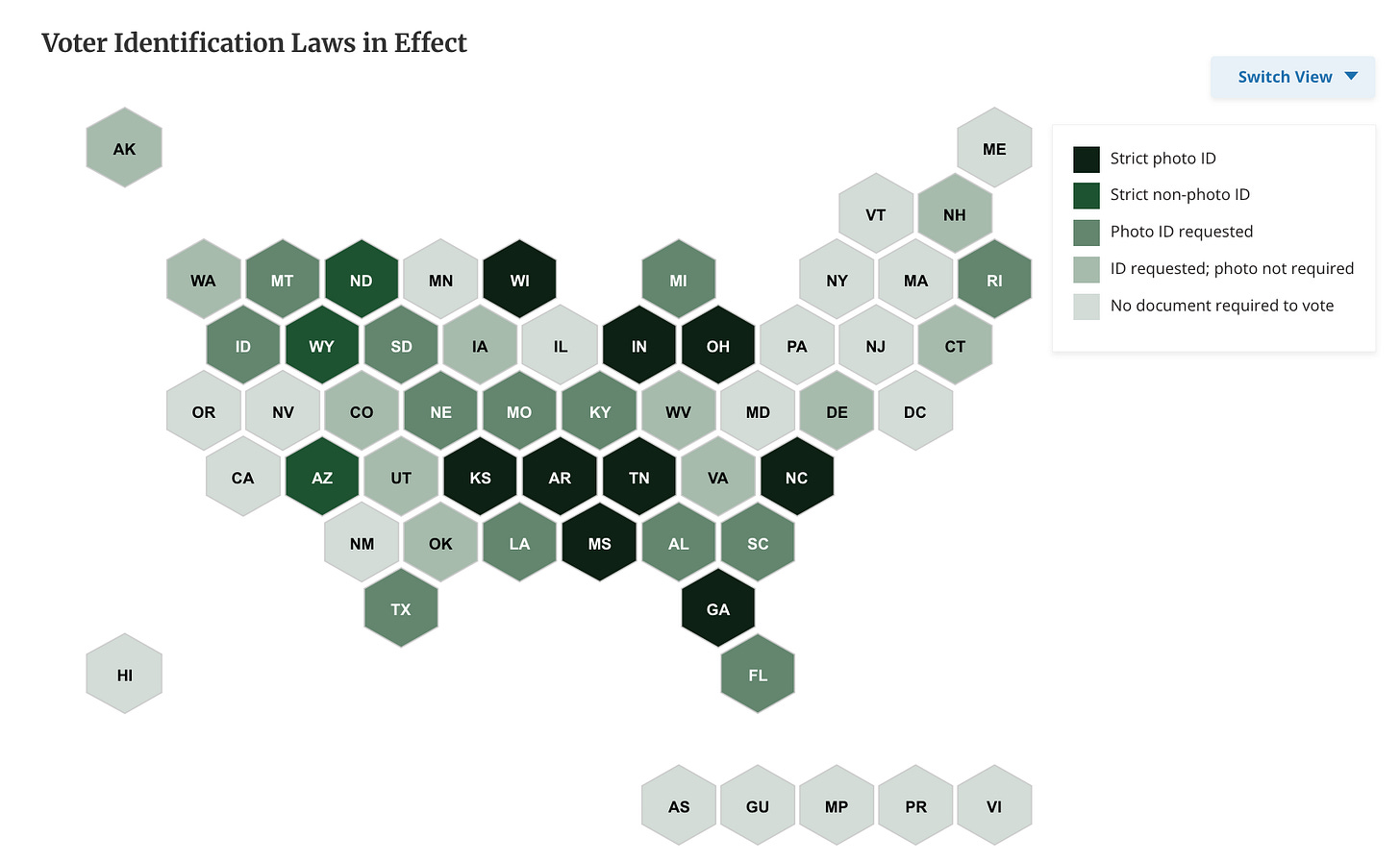

Furthermore, no federal statute dictates that voters have to offer identification at the polls during federal elections. Instead, each state determines its own voter ID protocols, resulting in a complex and varied landscape. Only nine states—Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Mississippi, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, and Wisconsin—implement stringent photo ID laws that prescribe government-issued identification and compel the use of provisional ballots for individuals unable to present one at the time of voting.

Several other states administer what are known as “non-strict” voter ID laws. In these jurisdictions, voters are requested to present identification; however, those who lack acceptable ID are still permitted to cast a regular ballot by certifying their identity—typically through a signed affidavit or verification by a poll worker. States operating under this model include Colorado, Florida, Missouri, Montana, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Utah, and Vermont.

Conversely, a number of states impose no ID requirement whatsoever. In places such as California, Illinois, New York, Oregon, Washington, New Jersey, Minnesota, Nevada, and others, voting can be as easy as verbally identifying oneself. In a hypothetical case of voter impersonation, someone armed with an American citizen’s full legal name, date of birth, residential address, and a passable imitation of their signature could arrive at the correct polling location in a state like New York, say “Hi, I’m John Smith from 123 Main Street,” and be handed a ballot. Unless the real John had already voted or arrived later only to discover his identity had been used, the impersonator would likely succeed—particularly if they knew John was indisposed and unlikely to show up.

What complicates the issue further is this: even the most commonly accepted form of identification in the U.S.—the driver’s license—conveys nothing about the bearer’s citizenship status. Many states issue driver’s licenses to lawful permanent residents, DACA recipients, foreign nationals, and, in some cases, undocumented immigrants. I speak from personal experience. As a non-citizen with legal status, I hold a valid New York State driver’s license. It allows me to board domestic flights and rent vehicles without issue, yet it reveals nothing about my immigration status or eligibility to vote.

The prevailing counterargument holds that, even in jurisdictions where voter identification is not customary at the polls, the American electoral system incorporates multiple layers of procedural protections. During the registration process, individuals are normally obligated to furnish their full legal name, date of birth, residential address, and a driver’s license number or the last four digits of their Social Security number.

Nonetheless, like driver’s licenses, Social Security numbers don’t authenticate citizenship. The Social Security Administration issues SSNs to all individuals authorized to work in the United States, irrespective of their citizenship status. As a result, non-citizens—including international students with on-campus employment—might legally possess SSNs while remaining ineligible to vote.

What the existing system primarily ascertains is bare-minimum eligibility: that the registrant is a real person, resides at the stated address, is of voting age, and is not simultaneously registered in multiple states. But unless a state undertakes the additional step of cross-referencing registration data against authoritative records—such as birth certificate databases, naturalization documents, or federal citizenship registries—there is no reliable mechanism for confirming a registrant’s citizenship status based solely on a license number or partial SSN. In practice, most states do not perform this level of verification.

To be fair, many critics of the SAVE Act are not engaging in bad faith. Their core contention is relatively straightforward: voter fraud—particularly voter impersonation—is statistically negligible. Over the past two decades, this view has been reinforced by a wide range of studies, including those conducted by the Brennan Center for Justice, academic institutions, and even Republican-led commissions. The consistent finding is that documented cases of such fraud are exceedingly rare.

Consider the incentives: a fraudulent voter risks fines, criminal charges, and prison for casting one illegal vote. There is no financial gain. No glory. No fallback. It is not exactly a career path. And even if a few individuals were willing to take such a risk, it would necessitate a massive, highly synchronized effort involving thousands—perhaps tens of thousands—of bad actors to meaningfully influence the outcome of a major election. Statistically, it is a high-risk, low-reward proposition with virtually no rational basis.

From this vantage point, the argument follows: why impose additional bureaucratic hurdles on millions of lawful voters to guard against a problem that, by all available evidence, barely exists?

It is a reasonable question—one that deserves careful and honest engagement. The bottom line is that many of the most vociferous assertions about voter fraud in the United States are driven less by empirical evidence than by political exigency. Allegations tend to surge in the wake of close or unexpected electoral defeats, where the losing side seeks an explanatory narrative. Isolated anomalies are magnified into systemic conspiracies. Ordinary clerical errors become proof of institutional decay. Fraud, in these moments, serves less as a documented fact than as a rhetorical device—effective not because it’s substantiated, but because it is emotionally and politically resonant. This is not to say that all concerns about electoral integrity are unfounded, but it does highlight how fraud—as a narrative—generally outpaces fraud as a quantifiable reality.

And yet, this brings us to an uncomfortable caveat: we may not have as firm a grasp on the true rarity of voter fraud as is often assumed. This is not an invitation to conspiratorial thinking, nor a contention that widespread fraud or stolen elections are the norm. Rather, it is a call for humility—a recognition of the methodological limits embedded in the very studies most commonly cited to downplay the issue.

Most empirical assessments—such as those conducted by legal scholars like Justin Levitt for the Brennan Center—depend on public records of prosecutions, credible allegations, and ballot rejections to estimate the scale of fraud. But these metrics are contingent upon detection mechanisms that are largely reactive rather than proactive.

To put it plainly, if an individual casts a ballot under someone else’s name or registers to vote despite ineligibility—such as non-citizen status—there is no automatic system in place to detect the violation unless it is incidentally flagged. Detection may only occur if, for example, the legitimate voter also attempts to cast a ballot or if discrepancies surface during jury duty screenings. In situations where such triggers don’t emerge, fraudulent activity can pass entirely unnoticed.

Consider the following cases, which illustrate longstanding flaws in the robustness of voter registration systems:

In 1998, the California Secretary of State reported that between 2,000 and 3,000 individuals summoned for jury duty each month in Orange County claimed exemption on the grounds that they were not U.S. citizens. Notably, 85 to 90 percent of those individuals had been summoned from the voter registration rolls.

Similarly, in a 2006 hearing before the House Committee on Administration, Maricopa County District Attorney Andrew Thomas testified that, after receiving a list of prospective jurors who had acknowledged they were not U.S. citizens, he proceeded to indict 10 individuals who had registered to vote—despite having attested to U.S. citizenship on their registration forms. Four of those individuals had, in fact, voted in prior elections.

More recently, in 2022, a Wisconsin resident named Harry Wait deliberately committed voter fraud as a means of exposing what he characterized as vulnerabilities in the state’s electoral infrastructure. Using Wisconsin’s online voter portal, he successfully requested absentee ballots for the Speaker of the State Assembly, the mayor of Racine County, and ten other individuals. According to Wait, he obtained the ballots by inputting publicly available birthdates and current residential addresses. Notably, this act of fraud was not detected by the voting system; it only came to light because Wait self-reported what he had done.

In this context, the absence of evidence should not be mistaken for evidence of absence. The electoral system operates on a foundation of presumed probity, sanctioning misconduct and punishing dishonesty only when it is uncovered. Yet, it does not actively authenticate voter eligibility across the board. Thus, if the system lacks robust tools for detection, low reported rates of fraud may reflect the limits of our observational capacity more than the actual security of the process. In other words, we might not be seeing more because we are not equipped—or not inclined—to look.

In that light, the SAVE Act is not merely a preventative remedy; it is an infrastructural one. Its aim is to establish a verifiable audit trail—a system that allows for the possibility of detection where, currently, there is none. Whether or not one agrees with the specifics of the legislation, its rationale is rooted in addressing the limitations of our current capacity to know what we claim to know.

Even if we were to place absolute confidence in the best available data showing that voter fraud is rare, one truth remains inescapable: perception is power. In any functioning democracy, legitimacy hinges not solely on procedural trustworthiness but on public conviction. If a substantial segment of the electorate believes elections are vulnerable to manipulation—rigged, stolen, or otherwise compromised—then the outcome, however procedurally sound, is tainted. A democratic mandate is not won by ballots alone; it is sustained by belief.

This is where the SAVE Act earns its keep. It is not a tool for deterring fraud alone—it is a structural assurance. An institutional signal that the electoral system is auditable, credible, and subject to scrutiny. It demonstrates to every voter, irrespective of political affiliation, that their ballot is cast within a framework that demands the same basic threshold from all participants: proof of eligibility, proof of citizenship, proof of right.

Why impose additional bureaucratic hurdles on millions of lawful voters to guard against a problem that, by all available evidence, barely exists?

This question sidesteps the broader implications. Across civic life, we routinely accept marginal inconvenience in pursuit of systemic security. Airline passengers submit to TSA screening not because each individual is presumed guilty, but because the risk of one bad actor justifies the precaution. Drivers carry licenses not because identity fraud is ubiquitous, but because shared infrastructure calls for enforceable standards.

The same logic applies here. Instituting documentary proof of citizenship is neither draconian nor discriminatory—it is a rational precaution. A proportional provision designed to reinforce trust, not erode it. And yes, it may entail a form, a certificate, or a return visit to the DMV. But what it yields is of far greater consequence: a democratic process armored against both malice and misinformation.

I am not an American citizen. Not yet. But I live here. I contribute here. And one day, when I finally earn the right to vote, I want that vote to matter—to carry the full weight of legitimacy. I want to step into a polling station with the quiet confidence that the system I am participating in is grounded not only in trust, but in truth.

When you come of age in a place where democracy was stolen, you do not take the vote for granted. You don’t mock safeguards as oppression or confuse verification with exclusion. You understand that democratic integrity is not a given—it must be constructed, tested, and proven. A democracy worthy of its name must be able to demonstrate that it can uphold the rights it professes to guarantee.

This is why I care. This is why I speak in terms of “we,” even though the law has not yet fully recognized me as part of the civic whole. Because I believe in the promise of American democracy, and I believe that promise is worth defending. And when I am finally permitted to take my place within that “we,” I want to know that the house I am entering has been kept in order—not merely for me, but for all of us.

So, I ask again, with the earnestness of one still waiting at the threshold: How much is liberal democracy truly worth?