Why Do the Loneliest Men Speak English?

Where other societies might treat romantic disappointment as a relational misfortune, the Anglophone world reimagines it as ontological destiny and transfigures it into community.

We call them incels—short for “involuntary celibates”—but the term barely captures the grievance-drenched, irony-poisoned subculture it now represents. These are not merely men who struggle to find intimacy; they are men who have weaponized their isolation into ideology. In the darker corners of the internet, they swap memes about “Chads” and “Stacys,” proselytize the nihilistic creed of the “blackpill,” and rail against a world they believe is hopelessly stacked against them—by feminism, by genetics, by modernity. Some wallow in resentment. Others veer into extremism. Several have erupted into mass violence.

What is most striking, though, isn’t just the rage. It is the language.

Most incels are Anglophone. Their memes, manifestos, and martyr-saints—Elliot Rodger, Alek Minassian, Jake Davison—arise not from some isolated subculture in a fragile state, but from the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and New Zealand. Why has this particular brand of alienated masculinity—at once self-pitying and aggressive—taken root with such ferocity in the English-speaking world?

A third-wave feminist might offer a familiar answer: “Systemic sexism and misogyny are still deeply embedded in many societies, especially non-Western ones, which means men there don’t experience the same perceived loss of status or entitlement. The Anglosphere, by contrast, is simply further along the arc of gender equality. Incel culture is the last gasp of patriarchy, not its strongest pulse.”

There may be some truth to that. But if the death throes of patriarchy explain English-speaking incels, then what accounts for Taiwan in Asia or Slovenia in Eastern Europe—two of the world’s most gender-egalitarian societies—where no man, to date, has taken incel ideology to its lethal extreme?

Loneliness is a universal aspect of the human condition, felt by people across cultures, languages, and histories. Nevertheless, loneliness does not always curdle into violence. Nor does it always metastasize into a self-justifying ideology of grievance. Around the world, we see expressions of male alienation—but rarely in the pernicious, ideologized form we have come to associate with English-speaking inceldom.

In Japan, for instance, there are the Herbivore men—young men who withdraw from dating, sex, and corporate ambition. That said, they are not angry at women. They do not blame feminism or modernity. They simply opt out, quietly and passively, in protest—or perhaps surrender—to Japan’s rigid expectations of masculinity and work. Their alienation is melancholic, not militant.

In South Korea, there is Ilbe, a far-right online forum infamous for its cocktail of misogyny, anti-feminism, and extremism. Ilbe users decry “feminazis,” mock victims of sexual assault, and promote crude nationalism. They blame feminism for South Korea’s low birthrate and supposed civilizational decline. And yet, despite Ilbe’s vitriolic speech—its harassment campaigns, doxxing, and threats—there is no record of an Ilbe user carrying out a mass killing in the name of sexual grievance.

In China, there are the so-called leftover men—a surplus demographic of rural, low-income bachelors who struggle to find wives in the aftermath of the One-Child Policy and a skewed sex ratio that prioritized sons. These men are notably marginalized, socially stranded. But their isolation, however tragic, has not yet coalesced into an internet-fueled death cult of romantic revenge.

Even in Eastern Europe, where one finds no shortage of anti-feminist rhetoric or ultra-Catholic nostalgia for medieval gender roles, there has been no incel-inspired bloodshed explicitly justified by sexual nihilism or male dispossession.

Unlike some feminists—whose theories often arrive in tidy packages, buoyed by the hubris of an enlightened Western narrative—I don’t believe incel ideology is merely the death rattle of patriarchy. It is, more profoundly, a symptom of modern Western life itself.

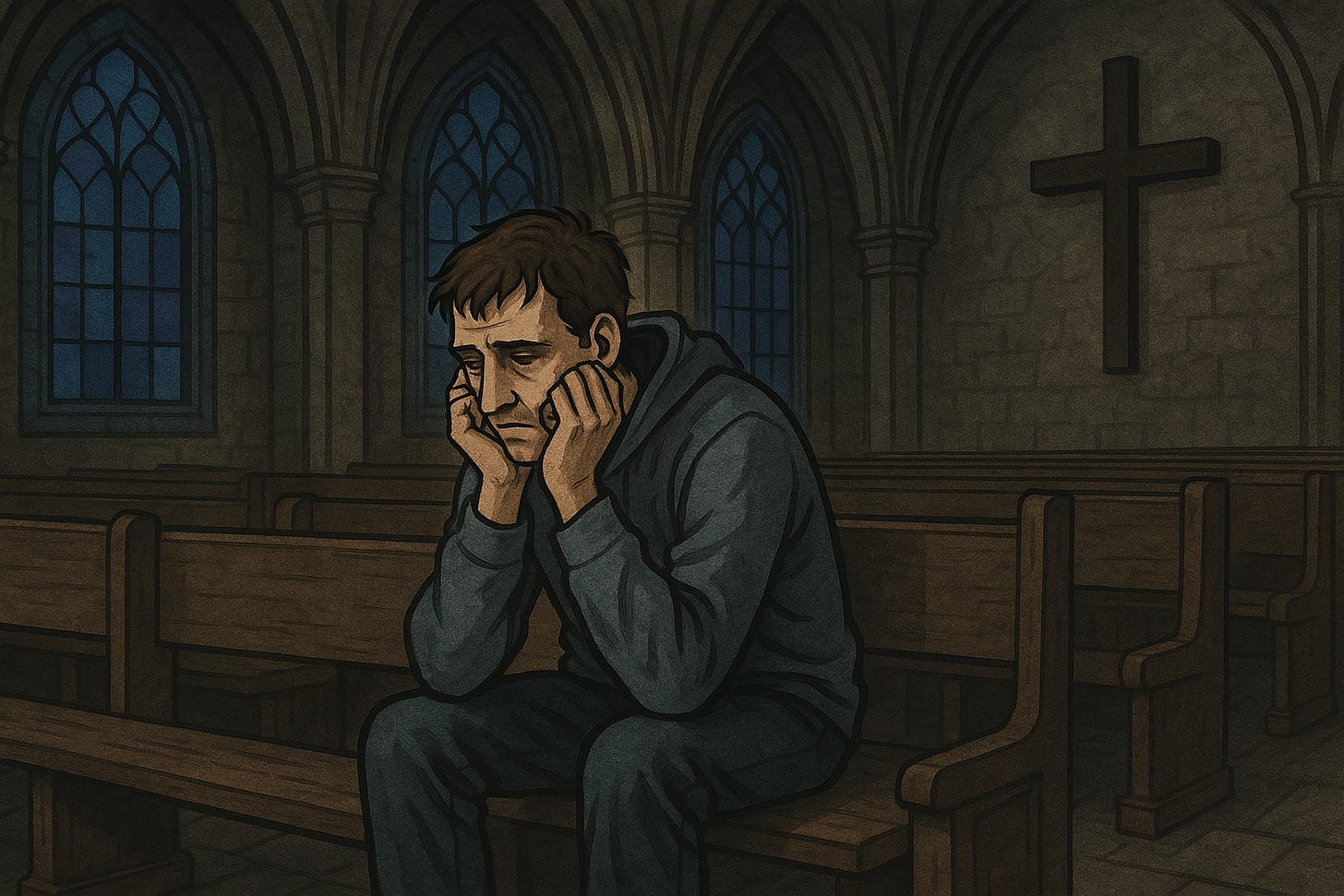

In traditional Catholicism, one’s relationship with God was mediated through priests, sacraments, and ritual. Believers confessed their sins to another. They performed rites. They belonged to a communal, embodied religious experience. On the other hand, Protestantism—the theological bedrock of North America and much of Western Europe, especially in its Calvinist and Puritan strains—placed a premium on solitary introspection. The believer stood alone before God. The diary replaced the rosary; the moral inventory displaced the liturgical calendar. The self became the confessional site.

As religious authority waned, this habit of inner scrutiny did not disappear. It was transmuted. What once spoke in the language of the divine has since been translated into the idiom of therapy. What had once been sin was sublimated into trauma. What had once demanded salvation now demanded healing.

As American sociologist Philip Rieff put it: “Religious man was born to be saved; psychological man is born to be pleased.” Rieff argued that modern therapeutic culture is, at its core, the secularization of the Protestant conscience. The soul gave way to the psyche; the confessional booth, to the therapist’s couch. Yet the struggle remained internal. The self must still narrate its inner torment, extract meaning from pain, and make its wounds legible—not to God, but to Reddit, TikTok, or Twitter therapy threads.

This Protestant inheritance converged with another: the liberal individualism that forms the philosophical foundation of Anglophone modernity. The self is sovereign—a property-holder of rights, an autonomous agent of self-fashioning, a lone pilgrim on the meritocratic ascent. John Locke’s political theory, the American mythos of frontier self-reliance, and the moral logic of personal responsibility all exalt the individual as both author and arbiter of their fate.

In its late-modern form, the Protestant–liberal inheritance has done more than liberate the self—it has unmoored it from the older scaffolding of meaning. What’s left is an atomized individual adrift in a competitive emotional economy, where suffering must be not only endured but displayed—explained, usually at length, and increasingly online.

This therapeutic impulse has undoubtedly fostered compassion and brought overdue recognition to mental health. However, woven into the grammar of English is a cultural script—one that urges us to psychologize every feeling, medicalize every hardship, and turn every private struggle into a publicly legible identity. Loneliness is no longer a passing season—it becomes a diagnosis, a role, a worldview. To be “incel” is not merely to be alone; it is to possess a pathology, a prognosis, and, in some cases, a martyrdom complex. Where other societies might treat romantic disappointment as a relational misfortune, the Anglophone world reimagines it as ontological destiny and transfigures it into community.

Indeed, it is the same emotional logic that underpins the identity politics that now dominate much of Western political life. Consider the category “Asian American.” It did not emerge from a shared civilizational lineage. Korean immigrants, Cambodian refugees, and Indian American families do not speak the same language, practice the same customs, or share a coherent philosophical tradition. What unites them—or what politicians seek to unite—is not cultural commonality, but a sense of collective marginalization, forged in the crucible of American grievance politics.

When a group identity is engineered from victimhood, it inevitably seeks both a culprit and a cure. Construct an Asian American identity around marginalization, and whiteness becomes the fortress to be stormed. Define LGBTQ+ identity through oppression, and cis-heteronormativity becomes the regime to be toppled. So too with inceldom: its ideological architecture hinges on a causal triad—women, feminism, and modernity—alongside an imagined solution—vengeance, retribution, or the collapse of society itself.

This dynamic is far less pronounced in cultures with a more normatively resilient collectivist framework. In Catholic-dominated Eastern Europe or Confucian East Asia, despair—though no less real—is commonly subsumed under broader obligations to family, nation, or tradition. In Poland, high religiosity and strong family structures serve as buffers against full-blown alienation. In South Korea, Ilbe’s acrimony, while corrosive, is bounded by a moral horizon shaped by conscription, nationalism, and a Confucian ethic that enshrines duty over the kind of self-expression that typifies Anglophone inceldom.

Although hyper-individualism and the decline of religion help explain the psychological soil in which inceldom grows, they do not reflect its geographic boundaries. Much of Western Europe—France, Germany, the Netherlands, the Nordic countries—scores just as high, if not higher, on metrics of personal autonomy, expressive freedom, and secular liberalism. These societies, too, have witnessed the retreat of organized religion, the rise of therapeutic culture, and the exaltation of individual rights. And yet, they have not birthed a homegrown incel movement with the same ideological cohesion or violent trajectory. There is no French Elliot Rodger. No German Jake Davison. No Swedish “blackpill” doctrine coursing virally through TikTok. Why, then, does inceldom remain so conspicuously confined to the Anglosphere?

One clue lies in the origin of the term itself. In 1997, a Canadian woman in her mid-20s—known only as Alana—created “Alana’s Involuntary Celibacy Project,” an online support group for people of all genders struggling to form romantic or sexual connections. This was the pre-social media era: no Facebook, no Instagram, no Tinder. Even MySpace was still six years away. Her forum was conceived as a virtual sanctuary for mutual empathy—a kind of proto-therapy circle for the socially isolated. Crucially, it was non-ideological. “Incel” was simply shorthand for “involuntary celibate,” a descriptor of circumstance, not a badge of identity or a blueprint for blame.

As the internet matured, so did the definition of the term. By the early 2010s, “involuntary celibate” had begun to circulate within male-dominated internet spaces—especially on Reddit, 4chan, and the constellation of websites collectively dubbed the “manosphere.” In these forums, the term shed its original spirit of support and took on a darker hue.

The pivotal moment came in 2014, when 22-year-old Elliot Rodger carried out a killing spree near the University of California, Santa Barbara. He murdered six people, injured fourteen others, and ultimately took his own life. His rampage involved stabbings, gunfire, and vehicular assault, but it was his 137-page manifesto, My Twisted World, that immortalized him within fringe digital subcultures:

“My orchestration of the Day of Retribution is my attempt to do everything, in my power, to destroy everything I cannot have. All of those beautiful girls I’ve desired so much in my life, but can never have because they despise and loathe me, I will destroy. All of those popular people who live hedonistic lives of pleasure, I will destroy, because they never accepted me as one of them. I will kill them all and make them suffer, just as they have made me suffer. It is only fair.”

In those pages, Rodger laid bare his hatred of women, his envy of sexually successful men, and his conviction that society had conspired to deny him the intimacy he believed was his due. Though he never used the word “incel,” the incel forums canonized him all the same. He became a grim icon, his face still circulated in tribute across the netherworlds of cyberspace. His words in My Twisted World were consecrated as a kind of scripture, defining the rhetorical contours of inceldom for the decade to come. What began as a descriptor of circumstance evolved into an identity—then into an ideology.

Others soon followed in his footsteps. In 2018, Canadian incel Alek Minassian drove a van into a crowd of pedestrians in Toronto, killing ten. Before his killing spree, he posted a chilling statement on Facebook: “The Incel Rebellion has already begun. We will overthrow all the Chads and Stacys! All hail Supreme Gentleman Elliot Rodger!”

At the heart of this ideological metamorphosis was the emergence of the “blackpill,” a term borrowed from the 1999 science fiction action film The Matrix and adapted to the epistemology of despair. Where redpill adherents believe the gender order is brutal but beatable—typically through alpha posturing, dominance rituals, or self-optimization—the blackpill offers no such hope. It posits a deterministic universe where romantic success is genetically preordained. Facial symmetry, height, bone structure—these are the arbiters of desire. Charisma is a myth. Self-improvement is delusion. Biology is destiny, and destiny is cruel.

It was this doctrine—fatalistic, totalizing, and self-reinforcing—that gave inceldom its hardened ideological edge. And it did not materialize in a vacuum. Anglosphere culture provided the soil: its Protestant inheritance, its liberal individualism, its therapeutic discourse. But it was Elliot Rodger—his manifesto, his language, his mythologization—who became the seed. His words distilled a raw emotional experience into a shared ideological script. And it was in English that this ideology first cohered, codified its terms, and metastasized online.

To understand why it has not yet taken root elsewhere, consider how long it took the concept of democracy to travel from ancient Athens to the rest of the world—not just as a word, but as an intelligible idea. The Greek demokratia—the rule (kratos) of the people (demos)—had no direct analogue in Latin. The Roman res publica (“public affair”) evoked a different civic architecture, grounded more in law than in popular sovereignty. It took centuries before Enlightenment thinkers in France, Germany, and Britain could meaningfully revive and reshape the Athenian model within their own philosophical grammars.

Liberalism followed a similar arc. John Locke’s theories of natural rights and self-ownership were not instantly portable across Europe, let alone to Asia or Africa. They had to be translated—linguistically, culturally, and ideologically. When Japanese scholars during the Meiji Restoration rendered “liberty” as 自由 (jiyū), it initially connoted “license” or “unrestrained will,” not inherent rights. It took decades of intellectual scaffolding before the Western concept of liberty could take root in Japan’s political consciousness.

So too with inceldom. It has not yet migrated because it has not yet been translated—not only in language, but in emotional syntax and cultural framing. There is no German equivalent of “betabuxxing” that captures the same cynical fusion of sexual fatalism and economic resentment. No French analogue for “Gigachad” that crystallizes, in a single meme, the apex male: enviable, unattainable, and the object of both hatred and aspiration. Even where echoes appear—on Ilbe, in fringe Chinese forums, among disaffected men in Brazil or Russia—they remain fragmentary, disjointed, untranslated in the truest sense: not yet absorbed into a native lexicon of victimhood.

Might that change? Possibly—but only in societies where the cultural soil is already tilled for such transplant. The Confucian ethic in East Asia, the post-Communist civic revivalism in parts of Eastern Europe, and the continued role of religion, military service, and extended family networks all mediate male alienation differently than in the Anglosphere. The emotional syntax simply does not align. There is no blackpill without a therapeutic culture to absorb it; no martyrdom complex without a digital confessional to sanctify it.

If this ideology is to spread, it will not leap from English-speaking societies to karst highlands of the Balkans, the windblown steppes of Central Asia, the rice paddies of the Mekong, or the red clay homesteads of sub-Saharan Africa. More likely, it will take root in the temperate loam of Western Europe, where ritual has yielded to secularism, where sadness is pathologized, and where liberal individualism has begun to eclipse older architectures of family, tradition, and shared telos. But even then, translation is not transmission. Something must still be lost—and something, if we are fortunate, may never be found.

For now, the loneliest men in the world speak English—because English, more than any other tongue, knows how to articulate their pain. It offers a vocabulary of nihilism, a dialect of introspection, and a vast cyber cathedral where existential dread is not just voiced but enshrined. Inceldom is, in many ways, a mirror. And the reflection it casts is not of broken men alone—but of a civilization, eloquent in its spiritual exhaustion.

Czech statesman Václav Havel once wrote, “The tragedy of modern man is not that he knows less and less about the meaning of his own life, but that it bothers him less and less.”

That, perhaps, is the quiet center of the crisis.