Why the Left Keeps Falling for Criminals

If oppression is systemic, working within the system is pointless. Reform isn’t a step forward—it is a concession. Real change, in this view, demands radical action, sometimes even violent revolution.

Once upon a time, criminals were cautionary tales. Bonnie and Clyde were outlaws, not influencers. Al Capone was a gangster, not a TikTok heartthrob. But today, crime doesn’t just pay—it builds a fanbase. Yesterday, it was Anna Delvey, the con artist whose deception bought her a seat at the table of high society. Today, it is Luigi Mangione, an (alleged) murderer. And leading the charge in this cultural rehabilitation? The Left, ever eager to add “nuance” where none is needed.

To be clear, the Right has its own brand of criminal worship—a subject I will dissect in a separate piece—but it manifests in a very different way. While the Right typically lionizes figures who project strength, defiance, or authoritarian power through political mythmaking that portrays them as defenders of order, the Left tends to glamorize criminals as misunderstood anti-heroes or victims of systemic injustice through cultural mythmaking, which aestheticizes them as celebrities.

But why? Why does this keep happening? Why does the Left, time and again, find itself drawn to criminals—not just as objects of sympathy, but as icons? The answer lies in a twofold dynamic: psychology and ideology. It is a particular psychological disposition that inclines people toward this pattern of thinking. And it is an ideological framework that both reinforces and attracts those with that disposition. Together, they create a feedback loop, ensuring that the cycle repeats.

At the heart of this phenomenon is what Canadian author Malcolm Gladwell, in David and Goliath, describes as the deep-seated human instinct to root for the underdog. This is more than just siding with the losing team; it is a cognitive bias that equates struggle with virtue and power with corruption. It is why Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey remains a universally resonant storytelling structure. Our brains are wired to see the scrappy outsider as the righteous protagonist, to believe that suffering must lead to redemption—that every hardship must, in the end, yield something good. But when this instinct collides with ideology, it mutates into something far more insidious: a blind veneration of the “oppressed,” even when their oppression is self-inflicted.

Take Anna Delvey, for example. Born Anna Sorokin in Domodedovo, Russia, she grew up in a working-class family before moving to Germany, where she struggled to fit in. By the time she arrived in New York, she had already reinvented herself—an outsider clawing her way into high society. She wasn’t born into wealth, she had no connections, and, perhaps most damning in elite circles, she had an accent. But instead of resigning herself to obscurity, she did what countless men before her had done—she hustled, schemed, and bluffed her way to the top.

Her trial peeled back the layers of a saga that hit all the right beats: an immigrant woman from humble beginnings infiltrating an exclusive, old-money world ruled by trust-fund babies and Wall Street sharks. It was not necessarily her crimes that captured the public imagination—it was the spectacle that could be staged around her. No wonder Netflix reportedly shelled out $320,000 to adapt her life into Inventing Anna.

To her starry-eyed defenders, she was more than a convicted felon—she was an anti-hero and a symbol of resistance. After all, in a city where finance bros and hedge fund bandits loot the world and float away on golden parachutes, why shouldn’t she get her cut? And as long as someone, somewhere, could be blamed for her misdeeds—capitalism, racism, sexism, the prison-industrial complex—accountability was just another rigged game to beat.

This pattern of thinking slots effortlessly into the broader leftist intellectual machinery, particularly the critical theory and intersectional doctrine that modern progressivism treats as gospel. Critical theory, birthed by the Frankfurt School, is obsessed with power structures—how they form, how they oppress, and, most importantly, how they can be torn down. It insists that all human interactions boil down to power and domination, reducing society to a crude binary of oppressors and oppressed.

Intersectionality—an ideological mutation introduced later by Kimberlé Crenshaw—stratifies additional grievances onto this framework, arranging race, gender, class, and sexuality into a rigid hierarchy of victimhood, where moral authority is granted based on perceived oppression rather than personal character.

As criminologist Bradley Campbell and Professor of Sociology Jason Manning argue in The Rise of Victimhood Culture, moral standing is no longer earned through merit but bestowed through suffering. In a world where power and privilege dictate who gets condemned and who gets a pass, Delvey’s identity functioned as a convenient shield, insulating her from full responsibility. (Check out my article, “The Moral Myopia of Woke Culture” in the Journal of Political Inquiry!)

Under this ideological scaffolding, criminals—especially those from marginalized backgrounds—are no longer seen as responsible for their actions but as helpless pawns of an unfair system. If power itself is the root of all evil, then anyone who lashes out against it—whether through fraud, theft, or even violence—can be rebranded as a radical freedom fighter rather than a common criminal. Their crimes become expressions of rebellion, and their punishments are reinterpreted as evidence of a punitive, unjust regime. This is why the tendency to rally behind the underdog finds such a cozy home in leftist ideology—it offers a prefabricated narrative in which even society’s predators can be depicted as David battling Goliath.

This conceptual foundation creates an intellectual sleight of hand: instead of judging individuals by their actions, leftist thought encourages a structural analysis that shifts blame upward. Personal agency dissolves under the weight of social forces. Crime is no longer about right and wrong—it is about power and resistance. When someone like Anna Delvey defrauds the wealthy elite, she isn’t just a scammer; she is a feminist icon who outplays the ruling class. When activists turn figures like George Jackson or Assata Shakur into martyrs, it is not because they care about the facts of their crimes—it is because those crimes can be woven into a revolutionary narrative that validates their worldview.

This is how psychology and ideology feed off each other in a self-perpetuating cycle. The psychological impulse to equate struggle with virtue makes people more susceptible to an ideology that rationalizes criminal behavior. In turn, the ideology attracts individuals predisposed to seeing the world through this lens, further cementing the pattern. The result? A culture where some criminals are not just absolved—they are exalted. Their crimes are laundered into political statements rather than moral failings, and their victims, when acknowledged at all, are dismissed in the war against “power.”

But here’s the problem: Anna Delvey didn’t scam “the system.” She scammed people—and not just the ultra-rich, but regular working professionals who got caught in her orbit. Her most infamous victim was Rachel Williams, a former Vanity Fair photo editor who believed she was Delvey’s friend—right up until she got stuck with a $62,000 bill for a Moroccan luxury vacation. Unlike Delvey, Williams wasn’t sitting on millions. She didn’t have a trust fund. And neither did Delvey. That was the entire con. She was never some anti-capitalist Robin Hood; she was just a grifter using the illusion of wealth to extract money from people who actually had something to lose.

Yet when Williams spoke out, she became the villain—mocked as a whiny Karen who should have known better. Inventing Anna went even further, portraying her as an opportunistic parasite. As The Independent put it:

The remaining four episodes are further nails in Rachel’s coffin. […] We’ve [the audience] received the message loud and clear: Rachel is a shady, social-climbing hypocrite who got what was coming to her. She’s a wannabe Anna, only without the guts or the clothes to pull it off.

In an interview with Vanity Fair, Williams was asked what troubled her most about the series. She replied:

The show’s trying to straddle the divide between fact and fiction. I think that’s a particularly dangerous space, more than the true-crime medium because people sometimes believe what they see in entertainment more readily than what they see on the news. It’s the emotional connections to a narrative that form our beliefs. Also, hunger for this type of entertainment urges media companies to create more of it, incentivizing people like Anna and making [crime] seem like a viable career path.

This is the dark underbelly of underdog syndrome: the moment people become so intoxicated by the fantasy of the misunderstood outsider, they lose all interest in the collateral damage. Delvey wasn’t outmaneuvering corrupt financiers or bringing Wall Street to its knees—she was stiffing hotel workers, conning friends, and leaving small business owners with unpaid bills. But that part of the story doesn’t fit the narrative. So, it gets erased, buried beneath the glitzy, Instagram-filtered legend of Anna, the fake heiress who never felt an ounce of remorse and openly reveled in the fact that crime, in her case, did pay.

Another powerful feedback loop between psychology and ideology stems from what is often called tabula rasa (blank slate) thinking—or what British writer and commentator Emma Webb refers to as the “Year Zero mindset.” Essentially, this mentality assumes that the existing system is irredeemably corrupt, that meaningful progress can only come by tearing it down and rebuilding from scratch—never mind what replaces it.

This perspective, especially prevalent among younger activists, intellectuals, and radicals, rejects gradual reform as inadequate and sees any compromise with the status quo as a betrayal of true progress. If something is bad, it must be obliterated—never improved. This is moral absolutism at its most theatrical, dressed up as revolutionary insight.

And, of course, it dovetails perfectly with the critical theory meta-narrative—the grand tradition of slapping a Marxist economic paradigm onto every facet of life. In their eyes, systems of power—capitalism, the state, law enforcement, even cultural norms—are not seen as flawed institutions that can be reformed but as mechanisms of control designed to uphold an entrenched elite. Incremental improvements, like civil rights legislation or labor protections, are dismissed as superficial fixes meant to pacify the oppressed rather than liberate them.

If oppression is systemic, working within the system is pointless. Reform isn’t a step forward—it is a concession. Real change, in this view, demands radical action, sometimes even violent revolution. This extreme approach isn’t merely an abstract theoretical quirk—it has deep historical roots. Figures like Lenin, Mao, Pol Pot, and Che Guevara embodied this exact mindset, championing revolutionary mayhem over sensible change, regardless of the human cost. And since progressive politics thrives on a sense of perpetual urgency, the call for sweeping, uncompromising overhauls becomes their raison d'être. Every hot-button issue—climate change, wealth inequality, racism, gender rights—is not just a problem to solve but an apocalyptic countdown that requires immediate, drastic action.

That is why, for instance, certain climate activists don’t just push for emissions reduction or renewable energy investment—they insist that capitalism itself must be dismantled to save the planet. The absolutism baked into this worldview ensures that any solution short of total systemic destruction is seen as treasonous. Pragmatism and compromise, then, become suspect, positioned as tools of the oppressor. Anyone daring to advocate for incremental change—whether moderates or center-left reformers—is unceremoniously ostracized as an enemy of progress, simply for suggesting that maybe, just maybe, civilization shouldn’t be reduced to rubble in the pursuit of ideological purity.

Few cases provide a clearer illustration of this phenomenon than that of Luigi Mangione. Mangione, a 26-year-old former data engineer, was apprehended in December 2024 for the assassination of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson. Authorities allege that he shot Thompson outside a Manhattan hotel before fleeing, leaving behind a 3D-printed firearm and a suppressor. His background—an Ivy League-educated engineer from a prominent Italian-American family—makes him an unlikely vigilante. But it is precisely this stark contrast between his privileged upbringing and his radical actions that has made him a cause célèbre for many on the Left.

Upon his arrest, police discovered a 262-word handwritten document in his possession. Widely referred to in the media as a “manifesto,” it stated:

I do apologize for any strife of traumas but it had to be done. Frankly, these parasites simply had it coming. A reminder: the US has the #1 most expensive healthcare system in the world, yet we rank roughly #42 in life expectancy. […] Obviously, the problem is more complex, but I do not have space, and frankly, I do not pretend to be the most qualified person to lay out the full argument. But many have illuminated the corruption and greed (e.g.: Rosenthal, Moore), decades ago and the problems simply remain. It is not an issue of awareness at this point, but clearly power games at play. Evidently, I am the first to face it with such brutal honesty.

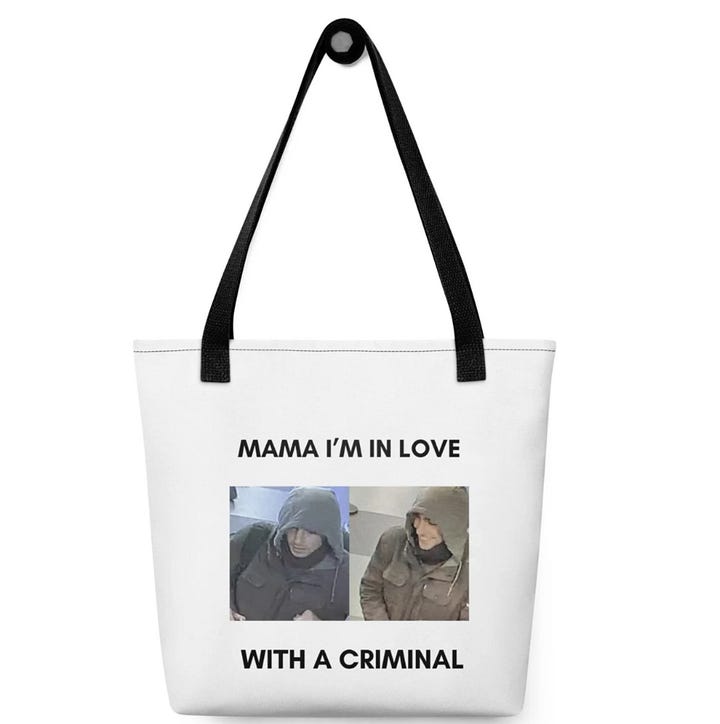

From hoodies to erotic fan fiction, the internet the internet is awash with fawning tributes to the suspected killer. Within hours of Mangione being charged, WIRED identified nearly 100 listings featuring products bearing his name or image. Among them: a tote bag emblazoned with photos of the alleged shooter and the phrase “Mama, I’m in love with a criminal,” and PDF mock-ups of Time magazine’s cover declaring Mangione Person of the Year with the tagline “Healthcare revolutionary, leading the charge to transform global health.”

Former Washington Post reporter Taylor Lorenz defended the public celebrations following Thompson’s murder in an article titled “Why ‘We’ Want Insurance Executives Dead.” She argued that in a country with “a barbaric healthcare system,” where “the people at the top…rake in millions while inflicting pain, suffering, and death on millions of innocent people,” it was only “natural to wish” that figures like Brian Thompson “suffer the same fate.”

In late February 2025, an enormous image of Luigi Mangione covered a building in Manhattan ahead of his upcoming court hearing. The image reads “Free Luigi” and depicts him as a saintly or Christ-like figure, touching a heart at the center of his chest with a halo around his head.

The allure of Mangione on the Left mirrors the pattern seen time and again: the willingness to excuse, rationalize, or even glamorize violence when it aligns with the right ideological framework. According to them, he is the perfect avatar of revolution—an intellectual who gave up on the dull, slow grind of reform and chose the more exhilarating route of bloodshed. His crime isn’t an atrocity; it’s an aesthetic. The thrill of revolution without the burden of governance. The fantasy of toppling institutions without the slightest clue how to replace them. He is the embodiment of the tabula rasa mentality, the perfect vessel for leftist ideology: Why work within the system when you can put a bullet in it instead?

The cold, hard truth is that in the entire history of human civilization, only one bloody revolution has ever resulted in a stable, rule-of-law-based government: the American Revolution. That wasn’t the norm—it was a freak historical accident. The French Revolution? It replaced a monarchy with a dictator. Napoleon Bonaparte, who started as a champion of liberty, ended up crowning himself emperor. It took France nearly a century—and the collapse of yet another empire in 1870—before they finally managed to cobble together a functioning democratic republic.

China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) was even worse. Launched by Mao Zedong to purge “bourgeois” and “reactionary” elements, it didn’t lead to greater freedom but instead deepened authoritarian rule. It decimated China’s intellectual, cultural, and economic foundations, leaving devastation in its wake.

This is why the most unsettling aspect of the Luigi Mangione hysteria isn’t just the romanticization of violence—it’s the blatant historical revisionism used to justify it. His adoring supporters absurdly liken him to Martin Luther King Jr., Mahatma Gandhi, and Nelson Mandela—leaders who actually built movements that changed the world, rather than indulging in a hollow, self-aggrandizing pipe dream of revolution-by-murder.

King and Gandhi were unwavering in their commitment to nonviolence, believing that moral authority came not from brute force but from perseverance, dignity, and the power to move hearts and minds through peaceful resistance. They didn’t pick up weapons or lash out in frustration; they worked within the system, using legal channels, public opinion, and civil disobedience to expose oppression. To equate them with a man who executed a corporate executive in cold blood is an insult to the very principles these leaders stood for.

And then there’s Nelson Mandela, whose legacy is routinely butchered by those who invoke his name without understanding it. Unlike King and Gandhi, Mandela did once embrace armed resistance, but that decision came after decades of peaceful protest were met with brutal suppression under apartheid—a system so violently oppressive that Black South Africans were legally segregated, disenfranchised, and treated as second-class citizens in their own homeland. Even then, when he finally walked free after 27 years in prison, he didn’t seek vengeance. He chose reconciliation, ensuring that South Africa transitioned to democracy without tearing itself apart.

To compare Mangione’s America—where activists, journalists, and politicians freely criticize the government without fear of execution—to apartheid South Africa is a grotesque distortion of history. In fact, Mangione isn’t even living in 1776, when revolutionaries were subjects of an empire ruling without consent. He isn’t under a government that has completely severed the social contract. He lives in post-Civil Rights Act America—a country where King had already proven that change is possible through legal recourse. He has options. He has rights. He chooses violence not out of necessity, but because it is easier than doing the hard work of making a difference.

This tendency to decontextualize the struggles of real revolutionaries and shoehorn them into a narrative that excuses any act of violence in the name of “justice” is intellectually lazy. It reduces the hard-earned victories of those who risked their lives for meaningful change into nothing more than aesthetic props for a cause that has no real strategy beyond destruction.

Even if one were to accept the warped premise that Luigi Mangione’s alleged crime was some grand act of justice, the uncomfortable reality remains: nothing about his actions budged the system he supposedly wanted to upend. The American healthcare crisis isn’t some mustache-twirling villain in a boardroom—it is an ingrained ecosystem of bureaucratic inefficiencies, regulatory capture, insurance monopolies, and a perverse pricing structure that insulates itself from competition. It is a hydra—cut off one head, and two more grow in its place.

Did UnitedHealthcare suddenly dissolve overnight? Did premiums drop? Did prescription drug prices plummet? Of course not. Brian Thompson was merely a replaceable cog in a machine that long ago abandoned free-market principles in favor of crony capitalism—where government intervention picks winners and losers, pharmaceutical conglomerates lobby for endless patent extensions and pricing protections, and insurance companies operate in cozy oligopolies shielded from real competition. Today, some other interchangeable corporate suit sits in Thompson’s chair, cashing the same paycheck, rubber-stamping the same policies, and, presumably, upgrading the office panic button.

If Mangione had truly wanted to strike at the root of the problem, his ire should have been directed at the web of regulations that prevent price transparency, restrict market competition, and incentivize bloated middlemen who drive up costs. Instead, he took the lazy, theatrical route: three bullets, a handful of news cycles fueled by terminally online leftists drooling over his courtroom photos, and a fleeting hit of viral adulation that changes absolutely nothing. The system grinds on, unbothered, while his fan club treats him like a tragic anti-hero instead of what he actually is—just another fool who mistook spectacle for revolution.

Hey, all Thought Criminals out there! I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Whether you agree, disagree, love it, or hate it, let me know in the comments—I welcome the debate. Thought Criminal is completely free, powered by my passion (and my full-time job), along with paid contributions to various new media outlets. If this piece made you think, challenged your views, or sparked a reaction, consider sharing it with your friends and stirring up some good old-fashioned discussion. Let’s keep the conversation going. 🚀🔥

Very interesting article, as usual. I’m curious to see how you’ll differentiate the manifestation of this tendency in right-leaning versus left-leaning individuals once the sibling piece is published.

I feel like outside of the choice of exactly which individuals are idealized and the specifics of who falls within the parameters of “victim” and “oppressor” within the underlying narratives at play—much of the contours of what you described here speak more broadly to the tendencies of anti-establishment political orientations in general (whether they be left or right in alignment).